Hereford

Christianity has old roots in Hereford: a Saxon bishopric was founded late in the 7th century and the original wooden church was replaced with a stone one, which became the burial place of King Ethelbert, at the beginning of the 9th century. This was replaced by a new cathedral, constructed early in the 11th century, which was destroyed by marauding Celts (Welsh and Irish!) in 1055 and remained in ruin until the arrival of the Normans. Following the Conquest, a new Norman cathedral was begun in 1107 by Bishop Reynelm and finished by Bishop Robert de Betun in the middle of the century. Compared with some other cathedrals, this was a relatively small, somewhat humble building constructed using local greyish/pink sandstone which appears to be somewhat harder than the red sandstone used elsewhere but, nevertheless does require frequent patching and repair.

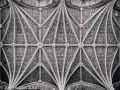

The massive Norman pillars and arcade in the nave and quire remain today from this church but, as in so many other cathedrals, expansion and rebuilding began almost immediately the original church was completed. And again, as is usual, the initial expansion was at the east end, starting with the addition of a retrochior and Lady Chapel in Early English Gothic, completed by 1220, followed by the Decorated eastern transepts and a new clerestory and vaulting to the quire, all completed by mid-13th century. The Norman quire now terminates at the east with a view of the massive central vaulting pier of the Lady Chapel vestibule.

In the 13th century Bishop Peter de Aquablanca added the beautiful north transept, with its innovative almost triangular pointed arches, dark Purbeck marble columns and fine wall decoration. The impressive central tower was completed about 1325 by Bishop Orleton, originally topped with a timber spire, which didn’t survive. By the end of the 14th century a Chapter House had been added, which no longer exists: the lead from it’s roof was stripped during the Civil War, it fell into disrepair and the stone was used in the 18th century by Bishop Bisse for alterations to his palace. At roughly the same time a series of fine misericords was added in the quire. In the 15th century, a tower was added to the western front of the nave, chantry chapels to Bishops Stanbury and Audley were completed, and at the beginning of the 16th century the North Porch was added as a major entrance to the church. However, despite the various additions, Hereford remains largely true to its solid Norman origins.

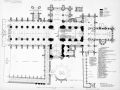

Hereford suffered significant damage and desecration during the Civil war, which was never adequately repaired or replaced. A major disaster (both physically and architecturally) occurred on Easter Monday, 1786, when the west tower collapsed, bringing down with it the entire west front and the western bay of the nave. This initiated serial rebuilding by a succession of different architects, much of it of dubious quality, through to the middle of the 19th century. James Wyatt rebuilt the west end, shortening the nave by one bay, (poorly) redesigning the triforium and clerestory, and installing a painted wooden vault (the floor plan from The Builder, dated 1892, shows the west front before and after Wyatt’s work). Further ‘improvements’ followed by Cottingham, who reworked the Lady Chapel and removed the medieval screen and many monuments, and by George Gilbert Scott who installed an inappropriate wrought-iron quire screen (thankfully removed in 1967). The work finally came to an end in June 1863 when the cathedral was formally reopened. In the 20th century, Oldrid Scott (son of G.G. Scott) rebuilt Wyatt’s west front to be more attuned to the original.

The massive Norman pillars and arcade in the nave and quire remain today from this church but, as in so many other cathedrals, expansion and rebuilding began almost immediately the original church was completed. And again, as is usual, the initial expansion was at the east end, starting with the addition of a retrochior and Lady Chapel in Early English Gothic, completed by 1220, followed by the Decorated eastern transepts and a new clerestory and vaulting to the quire, all completed by mid-13th century. The Norman quire now terminates at the east with a view of the massive central vaulting pier of the Lady Chapel vestibule.

In the 13th century Bishop Peter de Aquablanca added the beautiful north transept, with its innovative almost triangular pointed arches, dark Purbeck marble columns and fine wall decoration. The impressive central tower was completed about 1325 by Bishop Orleton, originally topped with a timber spire, which didn’t survive. By the end of the 14th century a Chapter House had been added, which no longer exists: the lead from it’s roof was stripped during the Civil War, it fell into disrepair and the stone was used in the 18th century by Bishop Bisse for alterations to his palace. At roughly the same time a series of fine misericords was added in the quire. In the 15th century, a tower was added to the western front of the nave, chantry chapels to Bishops Stanbury and Audley were completed, and at the beginning of the 16th century the North Porch was added as a major entrance to the church. However, despite the various additions, Hereford remains largely true to its solid Norman origins.

Hereford suffered significant damage and desecration during the Civil war, which was never adequately repaired or replaced. A major disaster (both physically and architecturally) occurred on Easter Monday, 1786, when the west tower collapsed, bringing down with it the entire west front and the western bay of the nave. This initiated serial rebuilding by a succession of different architects, much of it of dubious quality, through to the middle of the 19th century. James Wyatt rebuilt the west end, shortening the nave by one bay, (poorly) redesigning the triforium and clerestory, and installing a painted wooden vault (the floor plan from The Builder, dated 1892, shows the west front before and after Wyatt’s work). Further ‘improvements’ followed by Cottingham, who reworked the Lady Chapel and removed the medieval screen and many monuments, and by George Gilbert Scott who installed an inappropriate wrought-iron quire screen (thankfully removed in 1967). The work finally came to an end in June 1863 when the cathedral was formally reopened. In the 20th century, Oldrid Scott (son of G.G. Scott) rebuilt Wyatt’s west front to be more attuned to the original.